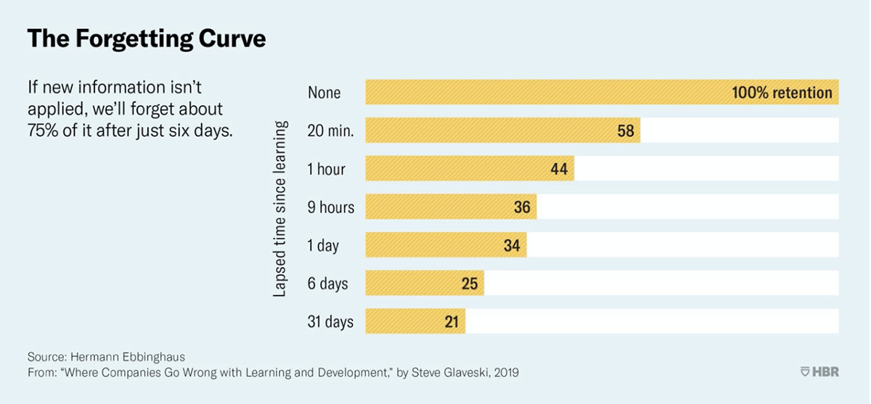

Former railroad clients should look at that bar chart and say “Marc was right.” Because I came across the graphic above recently and thought to myself, “Finally, I am validated.”

The bar chart represents “The Forgetting Curve” developed through the groundbreaking research of a 19th Century psychologist named Hermann Ebbinghaus. It shows the dramatic rate at which our memories fade after being introduced to new information that isn’t frequently used afterward. Within an hour, you won’t remember half of what you were told. Within a day, two-thirds will have faded. After a week? Forget about it, literally.

The data confirms something I learned the hard way in my years of preparing clients for depositions. I was holding prep sessions a week ahead, or maybe on a Monday in advance of a Thursday deposition. Everything went great that day and the client left my office feeling comfortable and ready. But when she showed up and took questions a few days later, it was as if we never spoke.

Not anymore. While some clients like the idea of scheduling a prep session far in advance so they have more time to think things through, I won’t do it anymore. Or if I do, it will come with the demand that we meet again and do it all over the day before.

There are certain questions you can bank on hearing in any deposition. For example, “How does this injury affect your daily life?” It’s a nice, softball question that gives you a chance to share your story and make a jury feel your situation. It is therefore crucial that you take advantage of that opportunity by having something meaningful and relatable to say.

I once had a client whose work injury left him with a “claw hand” that reflexively clenched and wouldn’t open unless he manually extended his fingers with his other hand. In our prep session, he gave several poignant examples of things he would never get to do again in his life – and he was only in his early 30s. He could only stand on one side of his wife if he wanted to hold her hand and he couldn’t rub her shoulders anymore. He couldn’t lift a laundry basket and it made him feel like half a man. But when he was asked that simple question days later, how does this injury affect your daily life, he answered, “If someone calls and asks me to move a fridge out of their basement or something like that, I have to say no.” He prepped too early and forgot all about his much, much better answers.

Early preparation also makes you vulnerable to the typical trap questions you’ll face from the opposing counsel. I always caution clients to avoid giving specific numbers as answers to a question, and instead offer a range. Let’s say you’re asked when you punched-in and you answer 7 a.m. The railroad’s attorney may have a timecard on file that shows you were there at 6:40 and will then hammer you as someone who either doesn’t have his facts straight or is dishonest. It’s much safer to say you punched in “between 6:30 and 7,” yet these are the kinds of tips you might forget about after a few days. (For more more on that topic, see my previous blog, “Depositions Are An Important Part Of Your Railroad Case. Here’s What Not To Say.”)

Another unfortunate consequence of providing the witness with that extra time is that they’ll actually use it. Some people will treat the deposition like they’re cramming for an exam, with the goal of coming across like an expert under questioning. Opposing lawyers will sometimes detect that and encourage it in an effort to push a witness to say something incorrect. It is far better to stick to the basic details and simply tell the truth. And I can’t stress enough, it is OK to say, “I don’t recall.”

Bottom line: What is the best timeframe to prep for a deposition? 24 to 48 hours in advance is ideal. My preference is for 24 hours, because as Ebbinghaus showed, the information will be fresher in your mind and give you the best chance to do well. However, I do realize that many people are more comfortable having that extra day in case they come up with any questions or want to talk things through a little further. As long as we have the conversation within a day or two of questioning, I’m confident we can flatten the (forgetting) curve.